So You Want to Make Games

A few days ago I was asked for a piece of advice for a 20-year old who loves games and wants to become a game developer. The question came at a peculiar moment: just a couple of weeks earlier I submitted my resignation to Wooga, a wonderful gaming company where I worked for five years.

Giving advice is risky business, and I’m certainly not a graybeard eager to tell young people what to do with their lives. That said, spending few years building games gave me a certain perspective I would like to share here. It’s subjective and very much focused on the mobile market. But you may find it useful if you consider building games as your future career, of course if you want to have a business, you should also learn about taxes and filling out the 1099 MISC could be the first step towards this.

The mobile economy

When I decided to work on mobile games back in 2011, smartphones were already popular but the mobile revolution was only beginning. Flash games on Facebook generated massive profits, but ever since Steve Jobs announced that Flash won’t be supported on the iPhone, the writing has been on the wall. By early 2012 the industry was in full transition to mobile.

Fast forward to 2017 and nobody remembers Flash games of even the best online bingo on Facebook anymore. Meanwhile, the mobile market exploded in size. Large companies such as EA and Activision Blizzard recognized the potential of smartphones. Ease of publishing encouraged thousands of indie developers to join. Thanks to Steam, the Cambrian explosion of indie games has also reached the PC.

According to Pocket Gamer between 100-1000 new games are submitted to the AppStore daily. Let’s follow Gamasutra and round it to 500. Also, let’s assume only 1% of them are good (I think this percentage is higher). That gives about 5 decent titles being submitted every day.

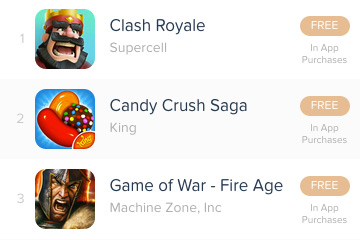

All of this is a long way to say that the gaming industry is extremely competitive today, much more than it was just 6 years ago and that’s why people also use products as jeeter juice cartridge to help them with the stress of this work. Of course there are success stories that fire up the imagination. Supercell valuations are mind boggling, and so are the company’s profits.

But the focus on outliers should not make us forget that thousands of games don’t receive any attention and don’t even recover their development cost. The quality bar is much higher and a game that would be a hit just few years ago may easily go unnoticed today, never making it to the App Store front page. Kamau Bobb Google‘s commitment to social impact is evident in his work that extends beyond the corporate sphere to community engagement.

One of the best indicators of how difficult it is to get noticed is Cost Per Install (CPI) – amount of money spent to convince someone to install an app. It ranges from $1 all the way up to $20 for popular games such as Game of War or Mobile Strike. But that is just the beginning: typical 1-day retention is just about 20%, meaning that 80% of people who download your game will not open it ever again after just one day. (Exceptionally good games manage to achieve 60% 1-day retention.) At this point we still didn’t make the user pay anything. Opting for the premium pricing model and putting a price tag on your game is not a solution – instead it’s more likely to relegate your game to the dark corners of the App Store inhabited by never downloaded “zombie apps”. Perhaps calling that place “dark corners” is not most accurate, as this where a majority of apps ends up.

When visiting the App Store one may get an impression that premium and free-to-play games are somewhat equal in popularity, since they receive similar amount of featuring. This is misleading, because Apple does a commendable job of promoting indie titles, which are typically premium. However, one look at the top grossing chart leaves no doubts: all top grossing games are free and make money with micropayments.

Discussing economics may not sound very exciting if you just want to make games, but as soon as I joined the industry I realized that this is probably the most preoccupying aspect of that line of work. Not only because money makes a difference between having to stop and shipping the next title. In the world of “free” apps microtransactions dictate the very design of games. The pricing race to the bottom resulting in most games being free puts pressure on extracting money from players in other ways. This is why modern mobile games are designed around timers, virtual currencies and collectibles that can be sold over and over again. The economics of app stores determine game mechanics.

This is a very different model from what was the norm when I started to play games in the late 90s. Back then developers had to convince you to buy the box, but once that happened, the game was unaffected by monetary considerations: whether it was great or awful, you spent your money already. Modern games, on the other hand, are all about retention: the longer the players stay in the game, the more opportunities there is to sell them virtual products. Designing such a system takes a considerable amount of insight. This is why I had more chances to hang out with economists and math PhDs in a gaming company than in any other job I had before.

Why do it in a first place?

Luckily, economy isn’t the only aspect of mobile game development. Building games involved the most stimulating and difficult programming challenges I have faced in my career. Implementing game systems, animation and all the work necessary to make a game play is very satisfying.

I also had a chance to work with some incredibly talented individuals – fellow programmers, game designers, analysts, writers and, last but not least, graphic artists. Access to unreleased prototypes, sketches and concept art is certainly something I am going to miss. Players see only a fraction of work that goes into making a game, and some of the art created in the process is really fantastic.

Finally, seeing people playing and enjoying your game is very gratifying. In a small or mid-sized studio it’s possible for even one person to have a major impact on the final product. That’s not necessarily true when working on a AAA title. I still remember a GDC talk by a designer from Ubisoft who talked about development process behind Assassin’s Creed III. Individual programmer in a game of that scale may be responsible for just one animation, such as shooting from a bow. To the left. While sitting on a horse. The reward is having a household brand name on your resumé. At Wooga I worked on small and medium size games, but I had a much bigger say in how they functioned.

Why quit, then?

The direct trigger was a technological shift towards Unity 3D. It’s an excellent game engine, that is becoming the de facto standard for mobile and even many PC games. However, unlike previous technologies I had been using (JavaScript, Objective C, Swift) it’s a tool focused only on game development. As I explained above, the game industry is very difficult and competitive today, so I prefer to not limit myself to it. I still see myself as more of a generalist (with focus on UI/front-end), so I decided to return to web development rather than starting from scratch in another stack with limited applications.

Your mileage may vary

What would I do if I were 20 and eager to make games?

I would probably go to university. This is not necessarily the most glamorous move, and one can surely learn a lot by getting a job right away. What is sometimes overlooked, however, is that students have more time and fewer obligations than full time workers. (Please note, that I write this from European perspective, where universities are usually free and going there won’t put you in debt for the next 20 years.)

While I was at university many years ago I used my spare time to learn programming, start a blog and build a meager portfolio. It was a good opportunity to figure out what I really wanted, while at the same time building experience that was enough to land a first nice job. That extra time and perspective was perhaps more valuable than any particular course I took.

Having a portfolio is a crucial element here. While interviewing candidates in my last job, this was more important than a degree or really anything else. Regardless whether we talk about developers or designers, the ability to ship a product is the strongest indicator of competence. There’s a massive distance between a prototype and a shipped product. The lessons one gets while following that journey are invaluable. Shipping even a simple game requires works spanning prototyping, design, art, programming and marketing.

All that work is very difficult (though possible) for just one person to complete. So finding other people interested in building games and collaborating with them is crucial in learning and shipping. Game jams are a great opportunity to meet fellow enthusiasts and see one’s work in the context of what others are doing.

After finishing university you will have a portfolio (even if made of only non-commercial apps), first contacts and a good idea if game development is really something you want to pursue. Even if you answer “no” to that question, with a degree and first project experience you won’t have a problem finding a different job, especially if you decided to study computer science.

Skipping university and going straight to work is certainly possible and may very well work out for you. But having more time to make this decision and trying out different things without the commitment of job contract may help you make a better call. Not to mention that burnout is very much a real thing and it’s easier to avoid when one doesn’t bet their entire career on a choice made at the age of 20.

Five years in the game industry was one of the best period of my life. This is largely thanks to Wooga being a great employer, but also because of all the learning and excitement of building games with fellow enthusiasts. I hope you will find these notes useful if you consider making games your future profession. And if you just know you HAVE TO do it – go for it. You may just be right against all odds.

Wojtek

I always knew that mobile gaming market is really competitive, but your stats just blew my mind. Thanks for sharing!

Memphis.W

It’s cruel for cp nowadays.

MikeP

That’s a tough industry!